On the roads of Tōhoku: a peaceful Japan, far from the crowds

A little-known region in northeastern Japan, Tōhoku still evokes memories of the 2011 earthquakes and tsunami for many. Scarred by this tragedy, this region remains unfairly overlooked by traditional tourist circuits. Yet, Tōhoku harbors a quiet strength, unspoiled landscapes, and a rare humanity. This trip, more emotional than touristy, offered me experiences of great intensity, in the heart of an extremely welcoming Japan.

Tōhoku, between mountains and solitude

Tōhoku stretches north of Honshū, Japan's large main island. It encompasses six prefectures, from Fukushima to Aomori, and remains one of the country's wildest and most rural regions. Here, there are no bustling megacities or hawking influencers, but lakes, mountains, and deep forests. A land of silence, often swept by the winds and covered in snow for months on end. It's also a territory shaped by a discreet history and tenacious traditions, which find little echo in major tourist guides. Even if winter must be magical, the large quantities of snow must make the trip considerably complicated. I visited in autumn, an ideal and very mild period, but the region must also be superb in spring, and undoubtedly very pleasant in summer when it's very hot everywhere else.

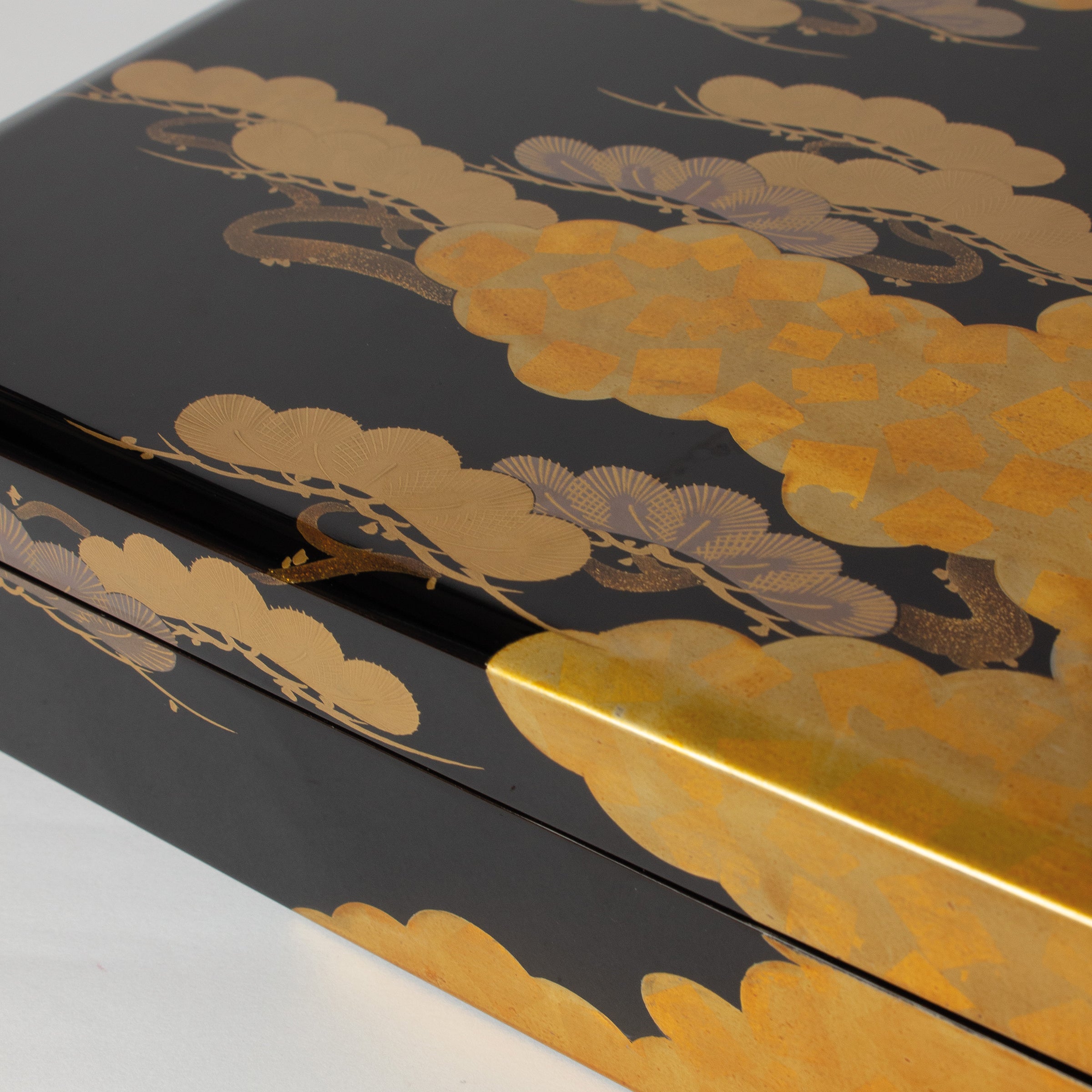

Tōhoku, a land of crafts and lacquerware

My trip to Tōhoku wasn't by chance. My journey was anything but a typical road trip. It was guided by a quest: that of lacquer artisans, discreet workshops, and rare techniques found nowhere else. The region boasts several renowned centers of the art of urushi , some of whose names, like Aizu-nuri and Hidehira-nuri, resonate with connoisseurs.

In these remote areas, the craftsmanship has retained a density, a purity, and a territorial anchorage that deeply moves me. Setting out to meet them meant straying from the usual routes, crossing isolated valleys, sometimes missing the "must-sees" in the guides... but this gave the journey a very special flavor. Tōhoku thus reveals itself, in fragments, through sensations, without revealing itself at first glance.

Travel in Tōhoku: Road Impressions

On the roads of Tōhoku, another image of Japan emerges. That of a country without designer cafes, without polished window displays, without crowds. A Japan without polish.

This is a hiker's paradise. Fewer historical sites, but breathtaking panoramas. It's the nature, the people, and the rural setting that strikes you at first glance. No hordes of tourists like in Kyoto, no crowds. Total tranquility. It's good for the soul.

It's also a perfect region for a first drive in Japan. Little traffic, very relaxed people on the road, sumptuous landscapes that remind us of the joy of driving at one's own pace. The only constraint: frequent road maintenance, but this doesn't detract from the smoothness of the journey. Outside the cities, the landscape becomes increasingly rural, sometimes even impoverished. We come across many abandoned houses, ageless buildings, neither truly old nor truly modern. The architecture evokes fairly recent settlements, almost like a "conquest of the North," a sort of gentle colonization of cold and isolated lands.

The locals, on the other hand, are disarmingly kind. Here, seeing a stranger still arouses curiosity, and often joy. In a tiny museum in Iwate Prefecture, I was alone with a class of five- or six-year-olds. For fifteen minutes, I was bombarded with questions. I taught them a few words of French. Their shrill "goodbye" (in French) still resonates in my memory. A suspended moment.

The abandoned houses and simple architecture are undoubtedly linked to the harsh climate. Winter conditions are extreme in this part of Japan: unimaginable quantities of snow cover roofs and roads every year. Traditional wooden dwellings cannot withstand the weather. They quickly rebuild, simply, and functionally.

This road trip lasted six days. I covered nearly 1,200 kilometers (much more than indicated on the map below), far too much for such a short stay, but my itinerary was dictated by the discovery of lacquerware centers, often very far from each other. I intentionally missed many sites mentioned in the guides, due to lack of time and choices, but it wasn't frustrating because I know I'll return. The goal was elsewhere.

6-Day Itinerary in Tōhoku: From Aizu to Aomori

Aizu-Wakamatsu(Fukushima Prefecture)

A quiet city, between nostalgia and slow modernization. In the often empty lacquer museums, one discovers ancient objects that leave one speechless. The history of lacquer is told without much pomp, often only in Japanese (thanks Google Translate!). Certain techniques, such as Aizu-nuri, are revealed in their diversity. In the evening in Aizu-Wakamatsu, there is an atmosphere that seems straight out of a Yasujiro Ozu film: a calm behind which one can guess the routines of daily life, a slightly nostalgic aesthetic, worlds that coexist. Knowing how to observe the imperceptible, an elegy of the banal that allows one to lift the veil of a Japan far removed from the stereotypical images with which we are inundated.

Yamagata (Yamagata Prefecture)

Away from the city, the village of Hirashimizu was the lovely discovery of this stage. A handful of workshops, perched on the mountainside and animated by birdsong. The potters work with local clay harvested from the slopes of Mount Zao. The kilns are discreet but welcoming, the shapes familiar. Nothing spectacular, but something just right. Here, one feels the deep connection between earth, fire, and custom.

Hiraizumi (Iwate Prefecture)

If I had to keep only one image of this endearing city: the Chuson-ji temple. It's still early, the temple has just opened its doors, there are smells of earth, humidity and incense in the air. I hardly meet anyone, except a cat, resident of the temple, who follows me and marvels with me. How is it possible to visit hundreds of temples in Japan and never get bored? Do you have to be formatted in a particular way? I once heard someone say "it's always the same thing." But nothing could be further from the truth, and you who love Japan know it well.

Chuson-ji is far from any typical tourist circuit, in the north of the main island of Honshū, in Iwate Prefecture, and slightly removed from a small town called Hiraizumi, whose existence I barely knew existed until discovering that it preserved a rich tradition of lacquerware craftsmanship. This temple was on my way before continuing north. It is one of my fondest memories of this trip to Tōhoku.

A softness, nature in all shades of green and large, dark and mysterious trees, scattered wooden pavilions where the only sounds come from the breath of the wind, the raindrops falling on the maple leaves and one's own steps that one would like to be as light as possible.

I come across a huge toad at the entrance to a small pavilion, just as surprised as I am by this unexpected encounter. There's a pavilion entirely covered in gold, hidden from view inside another pavilion, a treasure that isn't shared (in photos, anyway). Of course, the whole thing is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

As I left Chuson-ji, I wondered if I would ever see it again (that need to always return to beloved places!). Maybe not, but it will always remain a dazzling memory.

Kakunodate(Akita Prefecture)

In the old district of Kakunodate, the streets are wide, lined with black fences. Time passes slowly, as if slowed by the thickness of the walls. A former samurai town, it still preserves a dozen sublime historic residences, with low roofs and shaded courtyards, where moss covers the stones and maple trees lean tenderly toward the hedges.

The houses, some still inhabited, seem to watch over a silent memory. Some open to visitors, without unnecessary drama. We tiptoe in, greeted by the smell of old wood, worn tatami mats, and everyday objects still in their place.

In early autumn when I visited, the maple trees were slowly turning rust and fire. The air was fresher, clearer. The light was golden, low, almost melancholic. No crowds. Just the sound of footsteps on gravel and, occasionally, a creaking shutter. Kakunodate naturally imposes its quiet beauty, with muffled footsteps.

Tsuru-no-yu(Akita Prefecture)

While planning my morning route from Kakunodate to Morioka (Iwate Prefecture), I discovered Tsuru-no-yu (Crane Springs 鶴の湯), which wasn't listed in any of the guidebooks I'd read about the area. A hidden mountain hot spring, founded in the 17th century and once frequented by samurai seeking rest and healing, legend has it that a wounded crane was seen bathing in its waters to heal (hence the name): that was very inspiring!

The road to get there was sumptuous, becoming more and more winding, the last part resembling more a wide mountain path than a road. At the end, the impression that time had stopped in the 17th century: a few wooden houses and thatched roofs nestled in the hollow of a hill that displayed its autumnal hues in the background, the smoke from the outdoor baths and the heaters of the ryokan rising into the clear sky, a small impetuous river, a delightful end of the world, quintessence of a fantasized Japan, of a crazy charm.

Morioka(Iwate Prefecture)

A medium-sized city, without any obvious charm, but with some nice surprises, including the somewhat unreal sight of Mount Iwate, the “Mount Fuji of the North,” which we see approaching as the kilometers are swallowed up, a beautiful volcano with a cone almost as impressive as its illustrious cousin. Morioka is a city where we observe the work of cast metal, the patient gesture, the precision of the finishes.

Ninohe(Iwate Prefecture)

In the heights of Ninohe, hidden away in the twists and turns of small country roads, a forest of lacquer trees ( urushi no ki ), which alone justified this trip. A silent forest, an alignment of thin trunks striated with horizontal bands. The revitalization of these trees (today lacquer comes mainly from China) is so important. This is where it all begins, drop by drop, scar by scar. A few kilometers away, the Tendai-ji temple is deserted, there we come across jizō in red woolen hats who watch over the souls of children. Founded in the 8th century, this temple is at the origin of the region's lacquer tradition: the monks used and transmitted knowledge that shaped the local art of urushi . A monastic place, silent, lost in the vegetation. Nothing is staged. And that is precisely what is touching.

Kazuno(Akita Prefecture)

A modest stopover town, almost without any image, a destination frequented for its hot springs but without much charm, as if forgotten by the world. And yet, one of the great memories of the trip: a night and dinner in an exceptional guesthouse (to be found in the “where to sleep” section)

Odate (Akita Prefecture)

This is where magewappa , or "bent wood," is born, a 400-year-old Japanese tradition that involves cutting thin strips of cedar (most often), which are then boiled to soften them and then bent around custom-designed shapes. The workshops can sometimes be visited by appointment. You can smell the scent of cedar, the warmth of the hands, the precision of the gesture. The assembly and fixing of the elements is done using pieces of cherry bark. Each element is worked to be perfectly in harmony. The entire process lasts several weeks.

Hirosaki (Aomori Prefecture)

Hirosaki is a refined city, deeply marked by its culture. A former feudal city, with its castle, gardens, and temples, it has managed to preserve a living heritage. I hadn't initially planned to visit the Neputa Center. I was expecting it to be far too touristy, seeing the buses parked in the huge parking lot. In reality, it's quite the opposite. There you can see the immense lantern-floats of the Hirosaki Neputa Matsuri , a summer festival where they are pulled through the streets, accompanied by percussion and deep chants. Out of season, they sleep here, stored in the darkness, but still charged with tension. The painted faces (warriors, beautiful women in kimono, demons) seem ready to come to life at the slightest breath.

Tsugaru (Aomori Prefecture)

More than a city, a region of forests and mists. The hiba wood, typical of this area, is dense, fragrant, and insect-resistant. Used for construction and everyday objects. The sawmills are discreet but active. A noble material, permeating everything. Even the atmosphere seems different here: rougher, more mineral.

Aomori(Aomori Prefecture)

Last stop. Aomori is a new city, facing the sea and public transport. No old town, few traces of the past. One feels the wind, the cold, the approaching winter. One returns to modernity, to timetables, to trains. The Shinkansen heads south, to Tokyo and then Kyoto. We leave Tōhoku as if emerging from a slow dream, still enveloped by mountains, woods, and silence.

Renting a car and driving around Tōhoku

To get around I had chosen to rent a car from Nissan-Rent-a-car , because it is obviously, given the distances and the distance of the sites from each other, their isolation too, the easiest way to be totally free of one's movements. It is certainly not impossible to travel around Tōhoku by train and bus, the networks are always dense in Japan, but the schedules are more restrictive, of course, not to mention the places, in the middle of nature which does not see much public transport pass - if at all. So an option which requires having time in front of you.

As a reminder, in Japan we drive on the left (but the brain adapts very quickly from the moment the steering wheel is “on the right side”) and an international license is not enough, you need a certified translation of your national driving license, carried out in Japan, so it is essential to anticipate several months before departure. In France this translation can be carried out with the help of the Japan Experience agency. Once obtained it is valid for the entire lifetime of the driving license that was used.

From Tokyo I took the Shinkansen to Koriyama (1h40 journey) where I picked up the rental car, to avoid leaving Tokyo and the long road to Aizu-Wakamatsu, the first stop. You can ideally start the journey higher up, and take the Shinkansen to Sendai (for me Aizu was an important stop as part of my study of lacquerware, but on a “classic” Tōhoku discovery trip it is absolutely not essential).

Accommodation in Tohoku: tried and tested addresses

The choice of accommodation is quite limited, the region lacks structures, so the options are often business hotels close to the stations (no charm) or small guest houses (a great option but one that I tried to avoid because I didn't want to have too many time constraints for arrivals and departures).

I did a lot of research to find charming places, which sometimes required going to towns or villages I would never have set foot in, so I optimized the itinerary accordingly, so as not to waste too much time while still treating myself from time to time (because for me accommodation is never just functional, it contributes to the pleasure of the trip).

In Aizu-Wakamatsu: Ryokan Tagoto with a delicious (and gargantuan!) meal and an absolutely charming welcome. Can be booked on Booking.com

In Hiraizumi: Iris Yu is not exciting but functional and very well located. Can be booked on Booking.com

In Kakunodate: Machiya Hotel Kakunodate Great location, functional and well maintained. Book on their website.

In Kazuno (a small hot springs town in the middle of nowhere between Ninohe and Tsugaru): Yuzaka, a fabulous guesthouse with an amazing vegan meal. The best surprise of the trip! Book by email.

In Tsugaru: Komoru . In an area of no interest, an old renovated house full of charm, very atypical, magnificent room and superb meal. Can be booked on Booking.com