Japanese lacquer, the play of light and dark

"For a lacquerware decorated with gold powder is not made to be embraced at a glance in a lighted place, but to be guessed at in a dark place, in a diffuse glow, which, at times, reveals one or another detail of it, so that with the greater part of its sumptuous decoration constantly hidden in the shadows, it arouses inexpressible resonances."

Junichirō Tanizaki, "In Praise of the Shadow"

A story from the mists of time

The use of lacquer is the oldest traditional art in Japan, with a history that dates back to the Stone Age. The oldest lacquerware found in Japan is a 6,100 year old comb, whose red lacquer was still perfectly shiny! Japan is a land of trees, more than a third of the varieties of which exist only on the archipelago, on this volcanic land where they can flourish, a perfect mixture of rich soil and high humidity. From time immemorial, wood has been worked to magnify it, with unchanging craft techniques, whether for religious, residential or everyday purposes.

The most spectacular technique for using wood is undoubtedly that which starts with its sap, lacquer (urushi), initially used to protect and strengthen wooden objects, and which over time has become a craft of extreme complexity and refinement, fuelled by the demands of successive Imperial Courts, up to the Edo period which saw the development of maki-e (gold or silver dusting). From the Nara period (710 and 794) lacquer production was considered as important as silk or paper.

The vocabulary of Japanese lacquer art

URUSHI: this is Japanese for the sap of the lacquer tree. This sap is used applied to objects (to protect and/or decorate them) but is also used as a glue because it will harden when exposed to air and humidity. This is why urushi is also utilised as a base for the kintsugi technique, which allows objects (especially ceramics) repaired with this technique to last.

SHIKKI: Japanese lacquer craft

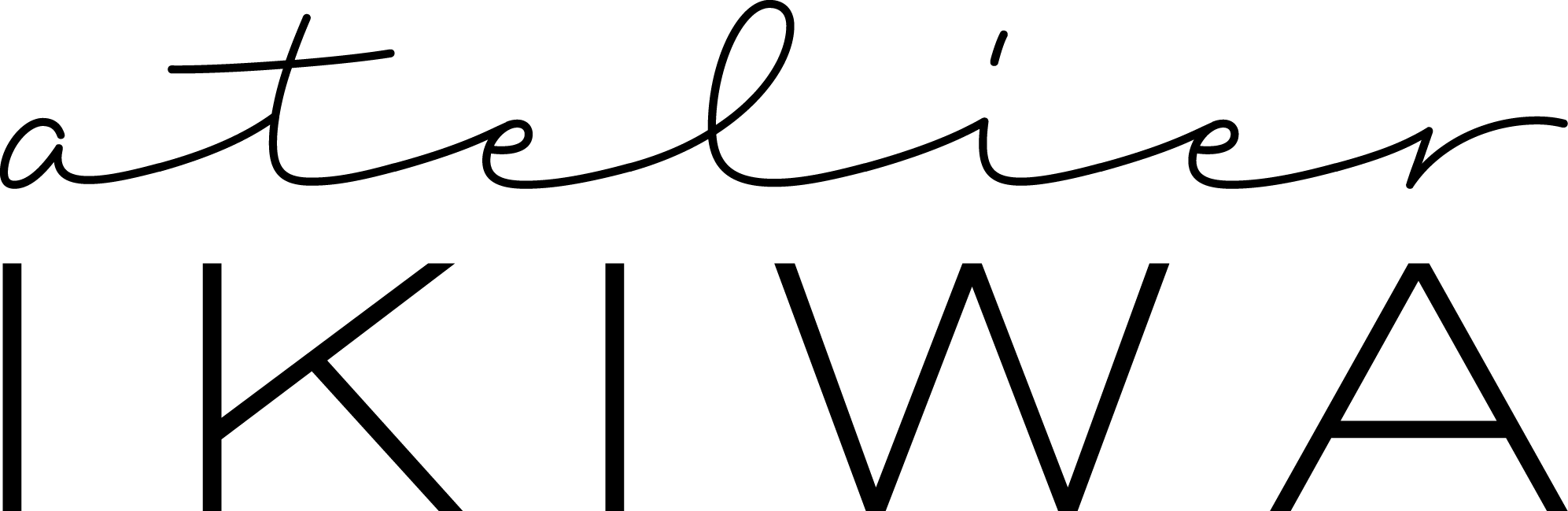

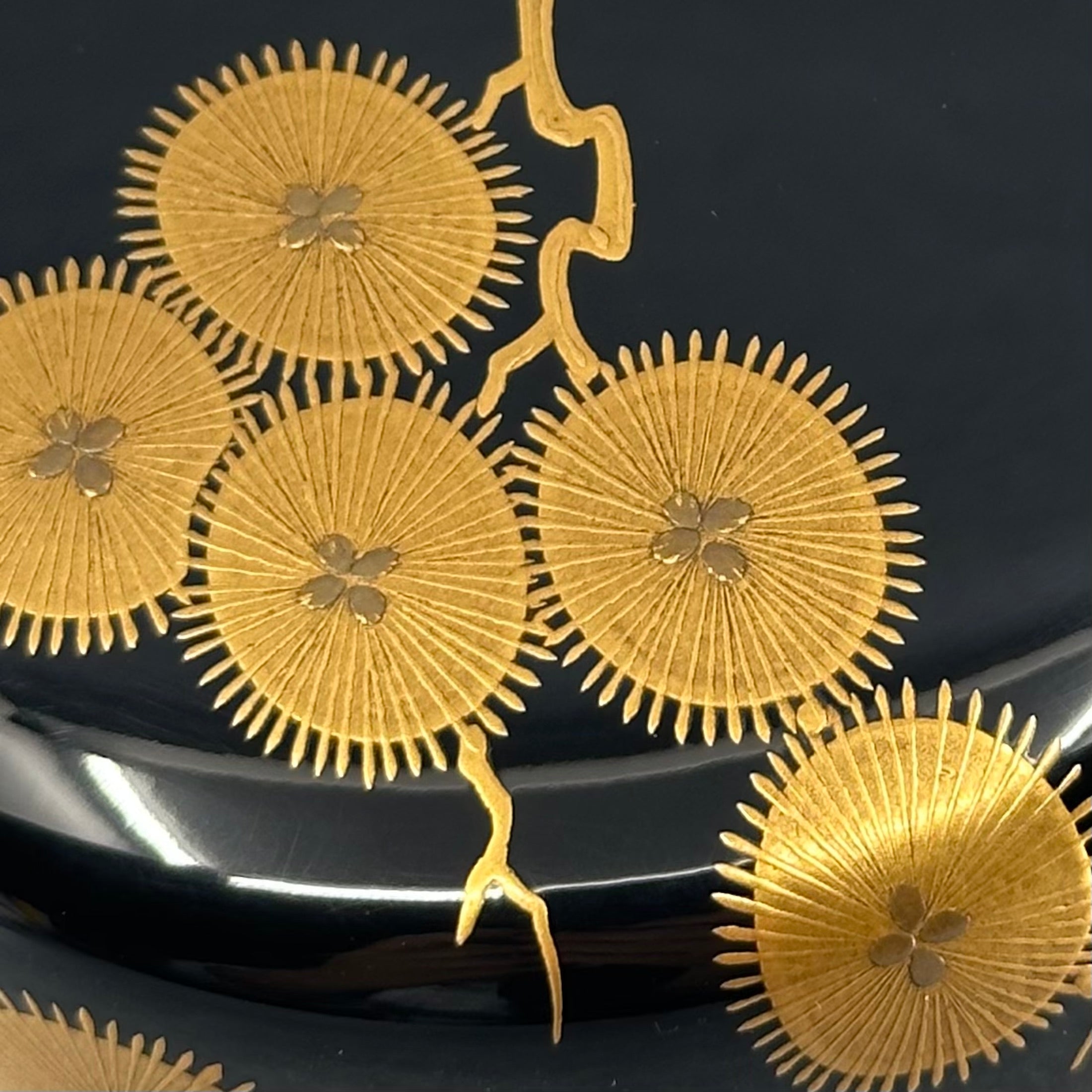

MAKI-E: the most refined technique used to magnify lacquerware, developed during the Edo period (1603-1868), which consists of creating a decoration on the lacquerware by adding very precious materials, such as gold, silver, mother-of-pearl, coral, semi-precious stones, etc. These materials can be sprinkled (gold and silver powders) on the lacquerware while it is still wet, or painted (gold paint), or inlaid.

The patient work of lacquering

At the beginning there is the sap of a tree, the Rhus Verniciflua, which grows in North-East and South-East Asia, but whose Japanese variant produces the lacquer considered the best because it contains the highest proportion of sparkle. The material is all the more precious because the tree is not very productive: only 200ml of sap in total can be harvested at one time from a tree that is more than 10 years old (which will then be replaced by a young tree that will have to reach its 10th year at least before it can give lacquer in turn).

Urushi lacquer is very toxic, and its toxicity only disappears once the lacquer has hardened (lacquer objects are therefore not toxic). To collect the lacquer, incisions are made in the bark of the tree and a white-grey viscous liquid is collected. After a process of filtering and dehydration the lacquer becomes transparent and pigments can be added to give it its black or red colour (the colours most often found, but the pigments which were natural until the 19th century made it possible to have yellow, green or brown lacquers too).

At the same time, the base for the lacquer is prepared: traditionally, lacquer is applied to objects that have been carved out of wood, but it can also be applied to paper, bamboo, textiles, metal, ceramics and, increasingly, to meet demand, plastic.

Highly specialised craftsmen

Each craftsman, who has years and years of practice before mastering his gesture, specialises in only one of the stages of making lacquer objects, because the precision and expertise required are the work of a lifetime of learning. The whole process is very slow and meticulous.

On the object successive layers of lacquer are applied. The more layers, the deeper and denser the result. On the contrary, a single coat will allow the wood grain to show through. As a rule, 3 coats are applied, but there can be 35 (or more!) with sanding between each coat. The last coat is transparent, applied on top of the decoration.

The decoration also requires great dexterity, with patterns that can be drawn and then painted, or sprinkled with gold or silver powder, or engraved.

Once exposed to the elements, air and humidity, the lacquer acquires all its qualities of hardness and durability, and the lacquered object will be ready to face the centuries to come without ever losing its quality!

The poetry of lacquer objects

Junichirō Tanizaki in his famous book "In Praise of Shadows" reminds us that Beauty is not found in the objects themselves, but in our relationship to them and especially in the play of light that allows the object to retain a part of mystery.

A lacquered object will always retain the aesthetic awareness of those who know how to take their time, to look at it, to appreciate it not just visually, but with all the senses: the softness of the touch of a lacquer, the depth and brilliance of a black which brings out the bright green of matcha tea powder, the contact of the mouth with a lacquer bowl (preferable for some to ceramics to appreciate the taste of things), the smell of wood and lacquer, the sound that escapes when one taps with one's fingernails on a lacquer object, a small delicate symphony.

A complete, unique and marvellous experience, of a quiet simplicity!

Discover our curated selection of Japanese lacquer objects here.