Japan, a land of wood: forests, spirituality and architecture

The Archipelago of Trees

With nearly 70% of its territory covered in forests, Japan is first and foremost a land of trees. From the mountains of Tōhoku to the slopes of Kyūshū, the landscapes are traversed by dense vegetation where cedars (sugi), cypresses (hinoki), pines (matsu), camphor trees (kusunoki), and paulownias (kiri) coexist. This abundance of forests, shaped by a humid climate and rugged terrain, has profoundly molded Japanese civilization: its spirituality, its architecture, its crafts, and even its imagination.

In Shinto thought, nature is not merely decoration but divinity. The kami, sacred forces that inhabit every element of the world, reside in stones, springs, and trees. Around shrines, the chinju no mori, protective forests, shelter these invisible presences and ensure continuity between the sacred domain and the world of the living. In these ancient woods, where nothing is ever cut without reason, man inserts himself with the utmost respect.

This organic relationship explains why, in Japan, wood has never been perceived as a commonplace or perishable material, but as a living, breathing, spirit-filled substance. It connects architecture to the cycle of life, both rooted and ephemeral, fragile and perpetual.

Wood and Impermanence

While the West built its cathedrals and monuments from stone, Japanese culture has always preferred wood. Stone seeks to defy the centuries, while wood accepts their passage. It expands, develops a patina, deteriorates, and is then reborn.

This vision is deeply linked to the Buddhist principle of mujō, the impermanence of all things. Building with wood means acknowledging that everything eventually transforms; it means inscribing beauty within the very fragility of the material. Fire, earthquake, typhoon—all these natural forces that threaten Japan have not led to abandoning wood (even though, of course, large cities have adopted more sustainable architecture to try to protect themselves from natural hazards), but rather to adapting it, making it a symbol of resilience.

Traditional carpenters have thus developed an art of flexibility: nail-free joinery, flexible structures capable of absorbing shocks, and millimeter-precise adjustment of beams and rafters. This expertise embodies a worldview: to build, destroy, and rebuild, not to erase the past but to prolong its memory.

Ise Jingū, the cycle of renewal

No place embodies this philosophy better than the moving Ise Grand Shrine, in the heart of Mie Prefecture. Dedicated to the goddess Amaterasu, it is considered the supreme shrine of Shinto. Yet, this venerable monument is, in reality, only about twenty years old: every twenty years, it is completely rebuilt according to an unchanging ritual, the Shikinen Sengū (the next reconstruction is scheduled for 2033).

This cycle of reconstruction, uninterrupted since the 8th century, relies on the use of hinoki (Japanese cypress), a remarkably pure wood with a tight grain and subtle fragrance. The hinoki comes from the Kiso forests, specially maintained for this sacred purpose. Each beam is selected, dried, polished, and fitted by hand. When the new shrine is completed, the old one is dismantled, and its wood is then reused for other shrines throughout the country or transformed into ritual objects. Nothing is lost: the cycle of wood extends the cycle of the world.

During a visit to Ise Grand Shrine, the emotion arises less from the splendor of the buildings (in fact, one can't see much, as the important structures are hidden from view) than from the invisible presence of the sacred. The scent of cypress, the golden light filtering through the trees: everything evokes the continuity between humanity, nature, and divinity.

Living wood

Even today, Japan remains a civilization of wood. Contemporary architects like Kengo Kuma and Terunobu Fujimori extend this tradition by working with wood as a breathable material, in dialogue with light and air. Their works—pavilions, houses, and museums—perpetuate this aesthetic of the living and the transient.

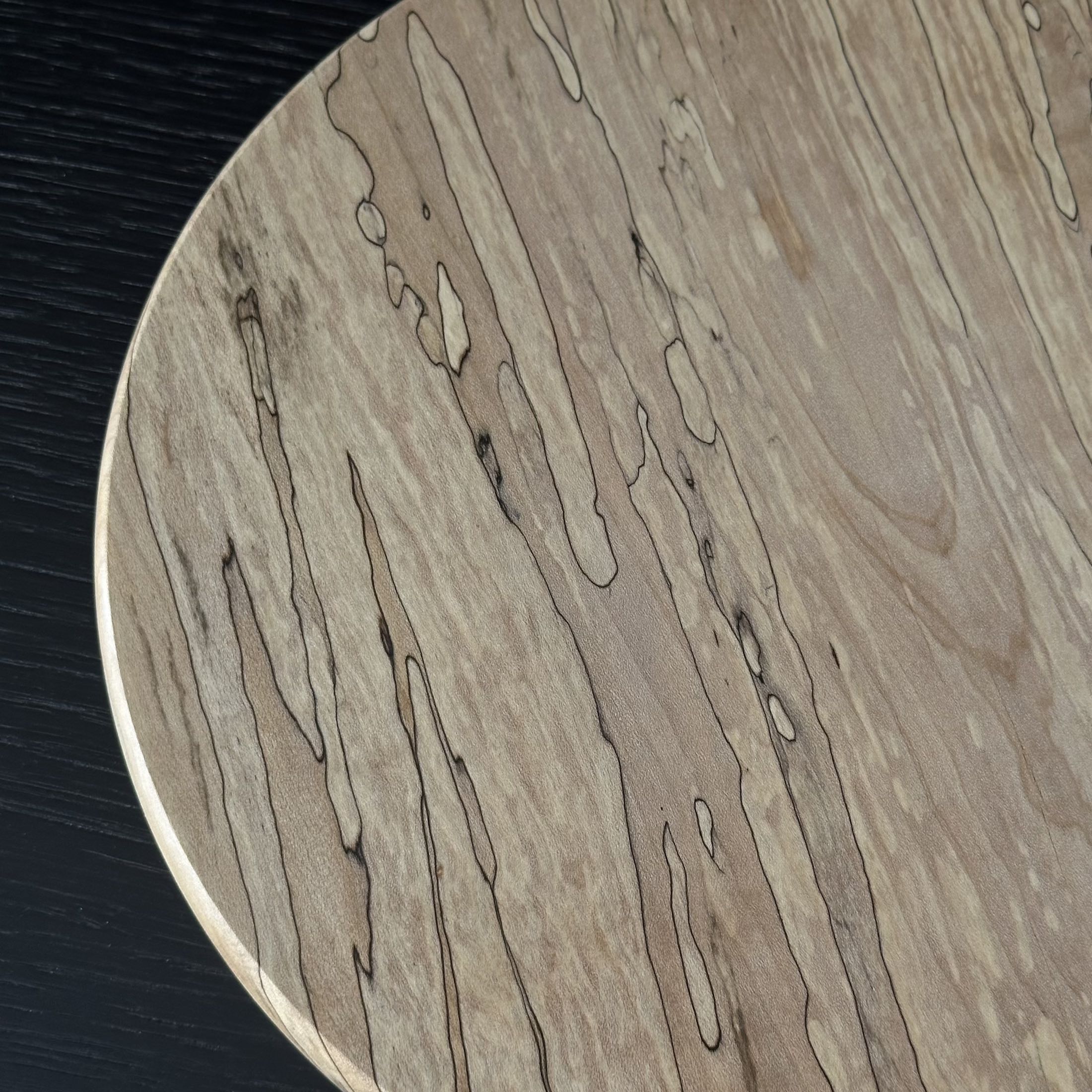

Wood remains central to everyday life. It structures space, softens light, and shapes objects used for tea, incense, or dining. It retains the memory of time, is polished by hand, and softens under a caress, as shown in the last photo of this article: the extraordinary platform of the Tenjuan Temple in Kyoto, whose entire history is read in the sumptuous grain of its wood.

Atelier Ikiwa is dedicated to promoting Japanese and Korean woodworking traditions by offering a selection of objects crafted by young artisans who reveal their unique character. These one-of-a-kind pieces, shaped using ancient techniques with a distinctly contemporary vision, extend the spirit of the forests from which they originate. They reflect the profound connection between nature, culture, and creativity in these two countries, where the forest links the sacred, the symbolic, and the everyday. We also invite you to read our article dedicated to the craftsman Sungwoo Choi , a very talented Korean craftsman.

Photos: © Atelier Ikiwa