Sekimori: The Guardian Stones of Japan

Atelier Ikiwa is proud to present, for the first time in France, the work of Eri, founder of the WARA brand, whose sekimori series we are showcasing. Eri creates pieces that unite stone and natural fibers, extending the ritual gestures of ancient Japan and inviting quiet contemplation into our contemporary interiors. We invite you to discover their origins.

The art of the threshold

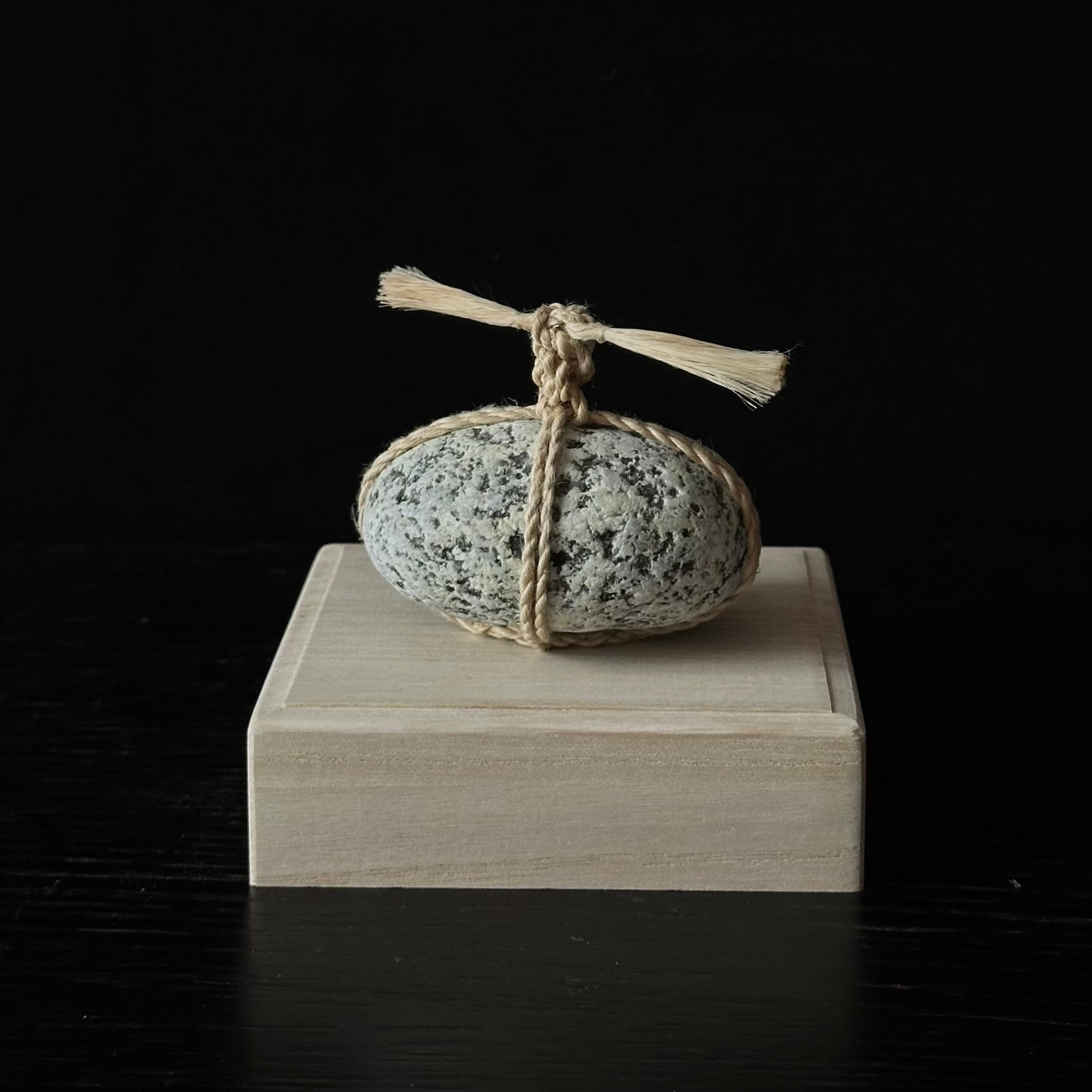

In Japanese gardens, certain stones, encircled by carefully braided rope, seem to guard the passage. Neither barrier nor obstacle, they simply invite one not to go any further. These stones, called Sekimori-ishi (関守石) or Tome-ishi (止石), belong to one of the most subtle gestures of Japanese culture: marking the boundary without constraining, preserving the tranquility of a space through the mere presence of a sign.

The Sekimori-ishi is inextricably linked to its braiding. Without this rope, knotted by hand according to a very ancient tradition, the stone loses its meaning. This rope is reminiscent of the shimenawa , the sacred ropes found in Shinto shrines, marking the boundaries of divine realms. Through it, the stone becomes a spiritual threshold, a focal point in the landscape.

A tradition born from tea gardens

The history of the Sekimori-ishi dates back to the 16th century, to the time of Sen no Rikyū, the founding master of the tea ceremony. In the gardens leading to the pavilion, called roji (“dew path”), visitors walk on stepping stones, the tobi-ishi , amidst moss and silence. At certain junctions, a stone encircled by a carefully braided rope is placed across the path: this is the Sekimori-ishi , “guarding stone.” It gently suggests the boundary of a space to be preserved, without words or constraints.

The Tome-ishi , "stopping stone," with its simple rope sometimes knotted in a cross, is its close relative. Used primarily in temples or certain passageways, it signals a closed or reserved space, always with the same Japanese restraint that prefers the sign to the panel.

Their difference lies in the intention (one interrupts, the other preserves), but in reality these two stones reflect the same philosophy: that of the conscious limit, of the passage between one space and another, between the movement of the world and inner peace.

A meeting in Kyoto

A personal anecdote: the first time I encountered one of these stones, a Tome-ishi in this case, I remember very well, was in front of the sublime Silver Pavilion in Kyoto, back when you could still get very close to it. The year 2000 was approaching, the garden was practically deserted, it was February, it was my first trip to Japan, and by sheer coincidence, Meryl Streep was also there, right next to me, in awe. A moment of stillness, like a communion, and this mysterious stone placed on a small bridge in front of the pond in which Ginkakuji was reflected. I understood its purpose later, but at the time it seemed to me to be an absolutely sacred stone, placed there to guide me on a spiritual path that I didn't understand but which struck me as extremely important, in this place that already contained an entire world.

WARA: Weaving the Threshold in the Contemporary World

It is within the tradition of sekimori stones and this art of the threshold that the work of Eri, founder of the WARA brand, whom I met during my last trip to Japan, finds its place. Touched by the meditative sensation of contact with rice straw, Eri began in 2020 to braid ropes inspired by shimenawa , those sacred ropes that adorn Shinto shrines and symbolize the boundary between the sacred realm and ordinary space.

Each Sekimori that Eri creates recreates this ancestral gesture: around a carefully chosen stone found on the beaches of Shizuoka Prefecture, where she lives, she hand-brides a rope of straw ( wara ) or purified hemp ( seima ). There are several ways to knot the rope, but it must be long enough to form a kind of handle. The braiding, done slowly, in the same direction as the shimenawa ( traditional stone carvings), imbues the stone with an almost spiritual tension. Eri creates scenographies and intentions that transpose ancient culture into the contemporary world.

The Ise Jingū Shrine: the heart of the sacred gesture

The Ise Jingū Shrine: the heart of the sacred gesture

Through her work, Eri echoes the spirit of Ise Grand Shrine, the spiritual heart of Japan, dedicated to the goddess Amaterasu, as well as the sacred Meoto Iwa rocks located nearby. These two places embody purity and the connection between the visible and invisible worlds. The Ise Grand Shrine, recognizable by its light wood structures, evokes simplicity and the perpetual regeneration of the sacred. The Meoto Iwa rocks, linked by a sacred rope ( shimenawa ) braided from rice straw, symbolize the union and continuity of the forces of nature.

Purified hemp ( seima , hemp cleansed of all spiritual impurities), used in the most solemn rites, represents clarity and inner strength. Rice straw, softer, evokes the warmth of everyday life and the rhythm of the seasons. It is in this spirit that Eri creates her braids, seeking the same harmony between tension and serenity, between strength and silence. Her Sekimori , crafted from purified hemp or rice straw, perpetuate this ancestral gesture of respect and awareness of space.

The Sekimori, stones for living

Eri's work is rooted in two essential notions of Japanese aesthetics. Ma (間) refers to the interval that allows forms to breathe, the space and time that exist between things. Yohaku (余白) is the beauty of the space left free, the white that reveals presence. In her Sekimori , stone and rope create this active interval and space, allowing the gaze to settle and the mind to find its center. These concepts, found in Japanese painting, calligraphy, and architecture, form the invisible framework of her work.

Placed in a cherished space, the Sekimori WARA create a breathing space, an inner sanctuary where the mind can refocus. By positioning them within the peaceful margins of daily life, they naturally find their place and provide calm companionship.

Placing a Sekimori stone in a minimalist space allows you to experience the Zen philosophy of yohaku (余白), the beauty of emptiness that creates balance. They offer a setting to calm the mind and savor the slowness of a tranquil moment. Today, these stones naturally find their place in contemporary interiors, on a table, a shelf, in the center of a room, or on a desk, where they alleviate the tension of a space.

Each stone is unique, chosen for its shape and presence, each rope hand-braided according to a know-how inherited from the Shimenawa . Their encounter forms a subtle balance between matter and silence, nature and consciousness.

WARA sekimori are available for the first time in France in the Atelier Ikiwa e-shop.

Photos: © Atelier Ikiwa