The Rimpa School: The Art of Poetic Stylization in Japan

Among Japan's great aesthetic movements, few have left such a singular mark as the Rimpa school (琳派). Neither an academy nor a hereditary lineage, Rimpa is a movement without a manifesto, born in Kyoto at the beginning of the 17th century, yet recognizable at first glance.

His works, whether painted or lacquered, are striking for their decorative power, their sense of rhythm, their ability to condense nature into stylized, free and luminous motifs.

This style, which has survived through the centuries without ever losing its freshness, reveals another way of thinking about art: not as an imitation of reality, but as a transcription of the essential.

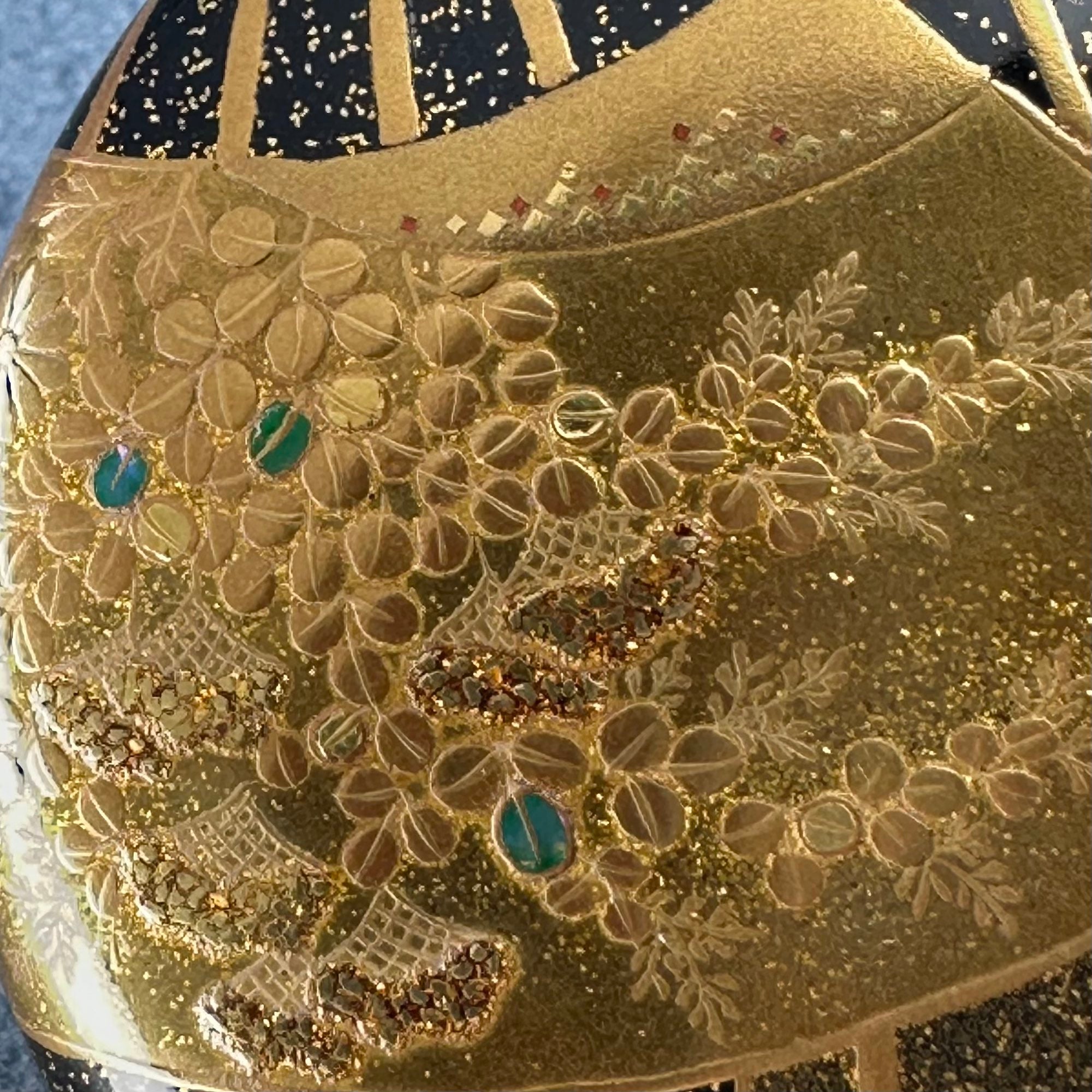

Ogata Kōrin School - Incense box with plum blossom decoration - 19th century - The Met Museum - Credit: HO Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. HO Havemeyer, 1929

Origins of the Rimpa school: birth of a style in Kyoto

The Rimpa school emerged in the city of Kyoto in the early 17th century, at a time when the aristocracy and scholars were redefining their relationship to the arts after the civil wars of the Sengoku period. It was not a school in the institutional sense, but an aesthetic movement driven by a shared affinity and admiration for ancient arts, particularly those of the Heian imperial court.

Two figures were at the origin of this style: Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558–1637), a calligrapher, potter, and aesthete from a family of sword polishers in the service of the shoguns, and Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active around 1600–1640), a painter and merchant established in the Shijō district. Together, they created works combining calligraphy, painting, and ornamentation, in which formal beauty took precedence over narrative. Their collaboration on illustrated scrolls of poems marked a decisive step in the birth of the style.

The union of the scholar and the artisan, of text and image, gave rise to an aesthetic based on the stylization of nature, the purity of forms, and the brilliance of materials. But what would later be called "Rimpa" did not begin as a manifesto. It was the artists of the following century, particularly Ogata Kōrin, who would crystallize the principles of this sensibility into a more immediately recognizable form.

Tawaraya Sotatsu - Wind God and Thunder God (17th century) - Kyoto National Museum. Credit: Brother Sun

Tawaraya Sotatsu - Wind God and Thunder God (17th century) - Kyoto National Museum. Credit: Brother Sun

A style that is primarily visual: aesthetic principles of Rimpa

The Rimpa style is distinguished by its visual immediacy. It seeks neither verisimilitude nor perspective, but offers a poetic transcription of the world, based on ellipses, stylization, and the free arrangement of forms. Nature is omnipresent, but it is never descriptive: grasses, waves, plum trees, and irises are reduced to the essentials, magnified by composition, voids, and contrasts.

Suzuki Kiitsu - Volubilis (early 19th century) - The Met. Credit: Seymour Fund, 1954

Rimpa artists favor flat tints of color, floating patterns, imperfect symmetry, and visual rhythms achieved through repetition or disruption. Space is structured not by a vanishing point, but by the breathing between forms. Movement arises from the tension between the stillness of the background, often gold, silver, or textured, and the dynamics of the patterns.

This treatment of the motif is part of the heritage of yamato-e, traditional Japanese painting centered on landscapes and seasons, and waka poetry, where suggestion prevails over description. The Rimpa style transposes the spirit into a visual aesthetic, where nature becomes a language of forms, rhythms, and silence.

Ogata Kōrin - Flowers - woodblock print - Edo period - The Met Museum - Credit: HO Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. HO Havemeyer, 1929

Lacquer in the Rimpa style: refinement of objects and brilliance of materials

While the Rimpa style was most prominent in screen painting, it also had a profound impact on the decorative arts, particularly lacquerware. Everyday objects such as suzuribako (writing boxes), kodansu (small chests of drawers), incense boxes, and trays became, under the influence of the movement, compositional surfaces in their own right.

Rimpa artists employ highly virtuoso techniques: maki-e, where gold powder is applied to fresh lacquer, raden, an inlay of iridescent mother-of-pearl, and nashiji, a shimmering effect achieved by dispersing fine metal particles in layers of lacquer. They also use cut or partially polished gold, silver, or lead leaves to create depth effects or emphasize the rhythm of the composition. These precious materials are not used for their material value, but for their ability to capture light and evoke a suspended beauty.

In these works, the motifs follow no narrative: they are fragmentary, suspended, sometimes asymmetrical, often linked to the seasons: camellias, irises, windswept pines. Ornament becomes language. The decoration does not complete the object: it transcends it.

Most of these pieces are unsigned. This is not anonymity, but a deliberate erasure of the individual behind a shared aesthetic. The Rimpa style, more than a name, is a spirit. It is not embodied in a single artist, but in a way of seeing and doing.

Ogata Kōrin School - Suzuribako - 18th century - The Cleveland Museum of Art - Credit: The Cleveland Museum of Art

Ogata Kōrin: The Master Who Crystallizes the Rimpa Spirit

A century after Kōetsu and Sōtatsu, the work of Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) marked a decisive step in the affirmation of the Rimpa style. Born into a family of wealthy textile merchants in Kyoto, trained in painting, kimono design, and classical culture, Kōrin brought to maturity an aesthetic based on the abstraction of reality and the tension between decorative splendor and formal simplicity.

His most famous works, such as the Irises or the Red and White Plum Trees, painted on screens, demonstrate this mastery of rhythm, silence, and surface. The contours are fluid, the volumes absent, the motifs reduced to the essentials. Each element vibrates through the contrast between the voids, the mineral pigments, and the flat areas of gold leaf. The painting becomes almost a visual fabric, a decorative score without anecdote.

Kōrin doesn't limit himself to painting: he applies these principles to objects, notably through lacquer boxes where gold, silver, and mother-of-pearl echo each other in floating compositions. Far from being a minor art, lacquer becomes for him a natural extension of painting, a space for refined experimentation. His brother, Ogata Kenzan, a renowned ceramist, extends this spirit into the world of everyday objects.

Through his influence, his fame and the breadth of his work, Kōrin gave his name to the movement: Rimpa, literally "Kōrin's school." This name, coined in the 19th century, came to designate a group of artists who shared the same sensibility, without a direct link from master to disciple, but linked by a loyalty to a common vision of elegance.

Ogata Kōrin - Iris to Yatsuhashi - Six-panel screen - 18th century - The Met - Credit: Purchase, Louisa Eldridge McBurney Gift, 1953

Heritage and extensions of the Rimpa style

The Rimpa style did not die out with Ogata Kōrin. A century later, in Edo, the painter Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828) set about reviving this heritage. Born into a family of cultured samurai, in 1815 he published Kōrin Hyakuzu (One Hundred Motifs of Kōrin), a series of prints celebrating the master's compositions. He also produced replicas and tributes to his works, while enriching the style with more delicate touches and more painterly nuances. Thanks to him, Rimpa became a transmissible, recognized, and reclaimed aesthetic language.

Beyond this 19th-century revival, Rimpa exerted a broader influence, even in Western art movements. Its stylization of nature, the decorative abstraction of its forms, the use of emptiness and precious materials inspired many European Art Nouveau artists, who were sensitive to this fusion of ornament, structure, and poetry. Creators such as Gustav Klimt, or schools such as that of Nancy, were influenced by this aesthetic from Japan.

Ogata Kōrin School - White poppies on a gold background - Six-panel screen - 18th century - The Met - Credit: HO Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1949

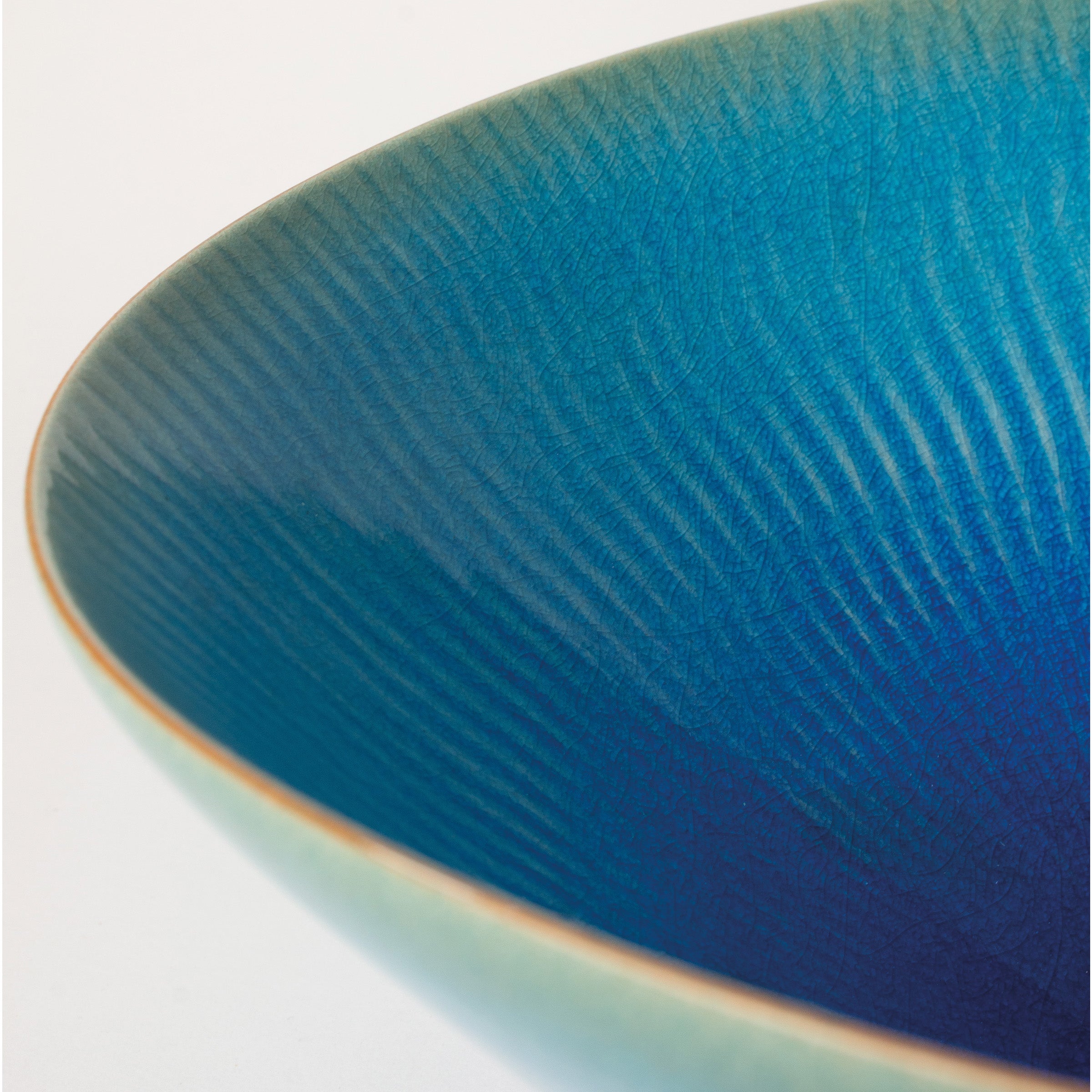

In Japan itself, Rimpa still permeates contemporary creation. It reappears in the graphic compositions of certain 20th-century painters, in textile design, ceramics, and even in installations and art objects designed by contemporary artists. Not as a fixed style, but as a visual grammar based on purity, repetition, and light.

Suzuribako Rimpa school, early 20th century, offered by Atelier Ikiwa, to be found via this link

Perhaps the strength of Rimpa lies in this ability to escape schools, while still leaving an imprint. It is not a doctrine, but a breath, recognizable without ever repeating itself.

Directly from the Rimpa school or other know-how that is perfectly anchored in our contemporary lives, exceptional Japanese objects can be discovered inour online store .

Attributed to Ogata Kōrin - Wisteria - Folding fan mounted as a kakemono - 17th-18th century - The Met - Credit: HO Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1949

Cover image: Sakai Hōitsu - Flowers and Plants Summer and Autumn - Two-panel screen - 19th century. Tokyo National Museum - Credit: emuseum